Soil sampling has traditionally been done in the fall, after crops are harvested. The objective is to know how much fertility the soil already has to produce next year’s crop.

But in my business, more than half my sampling is done in the spring. We usually begin sampling when fields are planted or ready to plant and continue until crops are no more than 12-inchs tall to minimize damage to the crop. I have found ATV damage to be minimal at this stage. The photo below shows corn has recovered a day after sampling.

One of the reasons for spring sampling is that the soil moisture and temperature conditions are usually more consistent in the spring. Moisture and temperature when soils are sampled can affect soil test results. That is the reason that experts agree you should sample at the same time of year every time you sample. In fall, soils can be dry and/or cold. I have seen potassium results as much as 75 pounds per acre lower when sampled dry as opposed to sampling later after soil is moistened by rain. I have not been able to find any problems with sampling wet soils if you are not cutting ruts.

Another advantage to sampling in spring is that results and recommendations can be ready before harvest to allow for earlier fertilizer purchase and more timely application. Application can follow the combine. With fall sampling, there is usually a delay between harvest and getting results.

Frequency of sampling is also an issue in the fall. The Illinois Agronomy Handbook says that once in four years is enough. The problem is that variations in crop yields because of dry or wet conditions may be difficult to account for when sampling only once in four years. We sample every year or two to take the guesswork out. If you base your fertilizer application on removal rates, keep in mind that your crop does not read the removal charts and removal is often more or less than the charts say.

No matter when you sample it is important to use proper techniques to assure consistent results. A soil probe and bucket are essential tools. Sample depth should be 7 inches in order to assure that your pounds per acre of nutrient is calculated correctly.

I like to sample in management zones, but the zones can be difficult to define for some people. Using USDA SSURGO data can be a place to start, but I find that about half the time it does not suit my needs. I like to use the five factors of soil formation to help me determine where the lines are between the zones. The factors include climate, organisms including vegetation, relief (or topography), parent material, and time. Yield maps can sometimes be used to determine zones. Some scientists like to use a Veris to measure electrical conductivity, which can define zones. I usually divide the field into major landforms and then subdivide to get 8- to 11-acre zones. I pull 10 to 15 cores over the zone to put less weight on old spread gaps and overlaps. Zones can be smaller if needed.

If you grid sample, you should still make sure the grid point defines the part of the field sampled. Avoid waterways or anomalies. Also, to avoid the old spreading gaps and overlaps, be sure to go 10 to 15 feet from your ATV and maintain that distance as you walk in a circle pulling 8 to 10 cores. There is a good bit of research that supports the need to pull many cores.

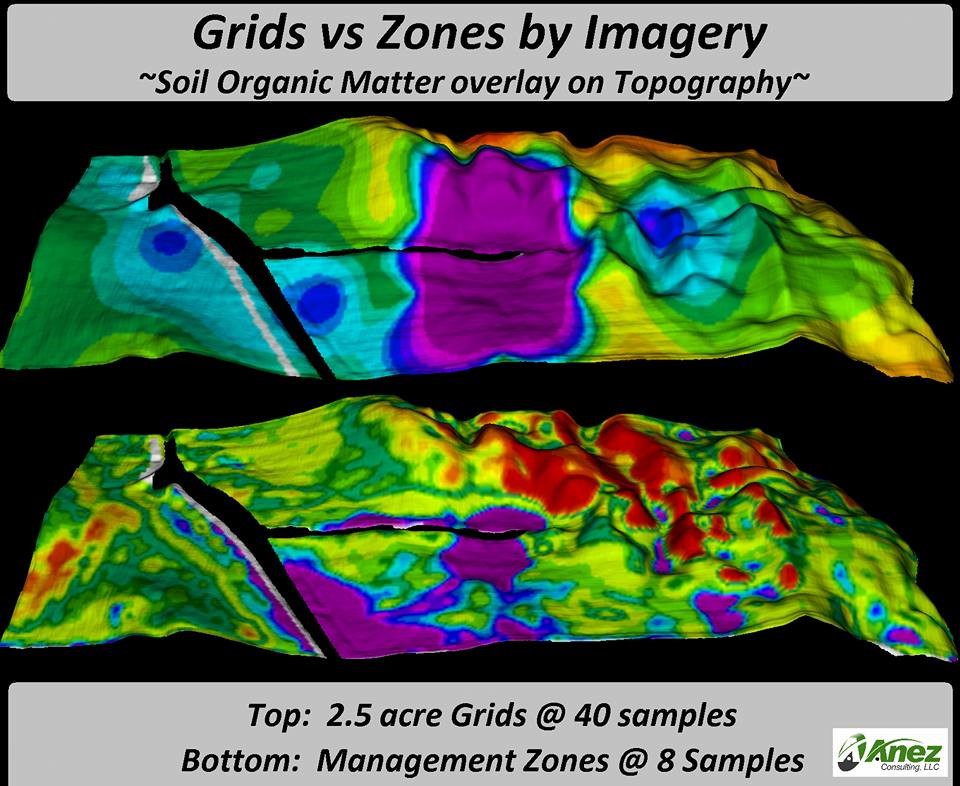

This illustration from Michael Dunn of Anez Consulting, LLC

in Little Falls, Minnesota, shows how grid sampling can distort what is in the field. (Courtesy of Michael Dunn).

Samples should be air dried. It is OK to use a fan but avoid heat over 125 degrees Fahrenheit.

Many people are considering switching corn acres to soybeans. One consideration is crop insurance. Check with your agent for help sorting it out. You may have a soil consideration with saturated soils if you have applied nitrogen for corn. Denitrification can occur fast on saturated soils. If there is nitrogen left, you may want to plant corn. You should soil test to see how much nitrogen remains in the soil. Your pattern for nitrogen sampling should assure that some of the cores are from the knife track and some are from the in-between areas. I get good results sampling a foot deep, but the University of Illinois says to sample 2 feet deep. Samples need to be spread out and fanned so they dry in 24 hours. You can also use an in-field nitrate tester, but they will miss the ammonium form of nitrogen. If you know you are not wasting nitrogen applied, you may not feel bad about switching to soybeans. If herbicides have been applied, make sure they will not cause a problem either.

The bottom line when growing soybeans is that you need to make sure that your fertility levels and fertilizer applied will support the high yields desired.

and then

and then