Insects are everywhere. For every man, woman and child on the face of the earth there are 200 million insects. In honor of National Pest Week, which is June 22-28, I thought I’d write my article this month about insects in soybean production.

When you hear the word insect, many people have a negative reaction. While there are certainly several insect pests in our world, there are generally many more beneficial species—that keep the populations of crop pests well in check—that we tend to glance over and not acknowledge.

Credit: Mississippi State Extension.

Insects go through distinct life cycles. Lady beetles are a good example of a complete metamorphosis. They begin as an egg and then hatch into a larva. The larva stage often feed on a completely different set of resources than the adult. Eventually they turn into pupa, which do not feed at all, before turning into an adult that reproduces and dies.

Some insects, such as stink bugs, go through incomplete metamorphosis. They hatch from their eggs, basically as miniature versions of their adult selves, and continue to grow.

In soybean production, it is common to see leaf feeding early in the season and think an insecticide application is needed. In actuality, most of the time if an unjustified application is made, we lost yield and net revenue from driving through the crop and buying unnecessary insecticide. Worse yet, we may accidentally destroy populations of beneficial insects, and allow the faster reproducing pest insects to cause much worse economic damage than if we did nothing at all.

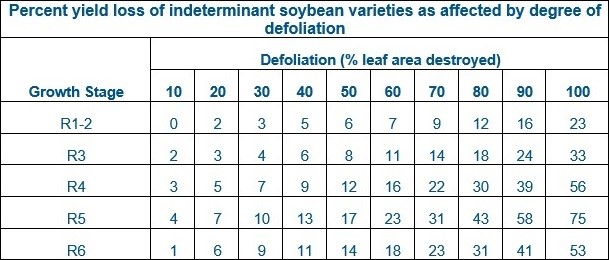

As you can tell by my charts below, it takes substantial leaf defoliation to have economic insect damage early season. Really, until grain fill ramps up the plant can sustain quite a bit of leaf feeding with very little economic damage. It is important to identify what insects are doing the leaf feeding, too. As I mentioned previously, if you find a larva, such as a caterpillar, defoliating your soybeans they may be close to pupa stage and quit feeding altogether on the crop very soon.

Chart from University of Nebraska Lincoln

Chart from Syngenta

Later season during grain fill, it becomes more important to keep your plants protected. Your crop can be especially susceptible to damage from aphids or stink bugs whose piercing sucking mouth parts rob valuable nutrients from the stems and pods of your soybean plants. Even if you find these pests in your soybean fields, it is important to check economic thresholds and check for populations of beneficial insects.

of California

The most common scenario where insecticides are applied too early is when aphids are observed feeding on soybeans, but there is a healthy population of lady beetles and lady beetle larva to prey on them. After an insecticide application is made, the aphid population may explode because they reproduce much faster than the lady beetle population.

Similarly, populations of assassin bugs and minute pirate bugs are slow to rebound after an application of insecticide. Assassin bugs prey on stink bugs and a whole host of insects. Minute pirate bugs feed on aphids, spider mites, caterpillars, and several species of pest eggs.

So the next time you see insects in your soybean fields, stop to look at all species present and closely examine IPM guidelines to see if a spray is warranted. You’ll likely be surprised at how often it isn’t. You should also contact your local Illinois CCA to learn more about the different types of insects, understand which insects can cause a yield impact, and to understand how beneficial insects can help protect your crop.

and then

and then