While there are many variations of the proverb, the most common might be that March weather “comes in like a Lion and goes out like a Lamb”. March is a transitional month for us in Illinois when we leave meteorological winter and enter the spring season. The active winter jet stream, which remains strong through February and March, contributes to increased storminess across the state. Rain, snow, thunder, and everything in between is on the table as far as observable weather phenomenon across the Midwest.

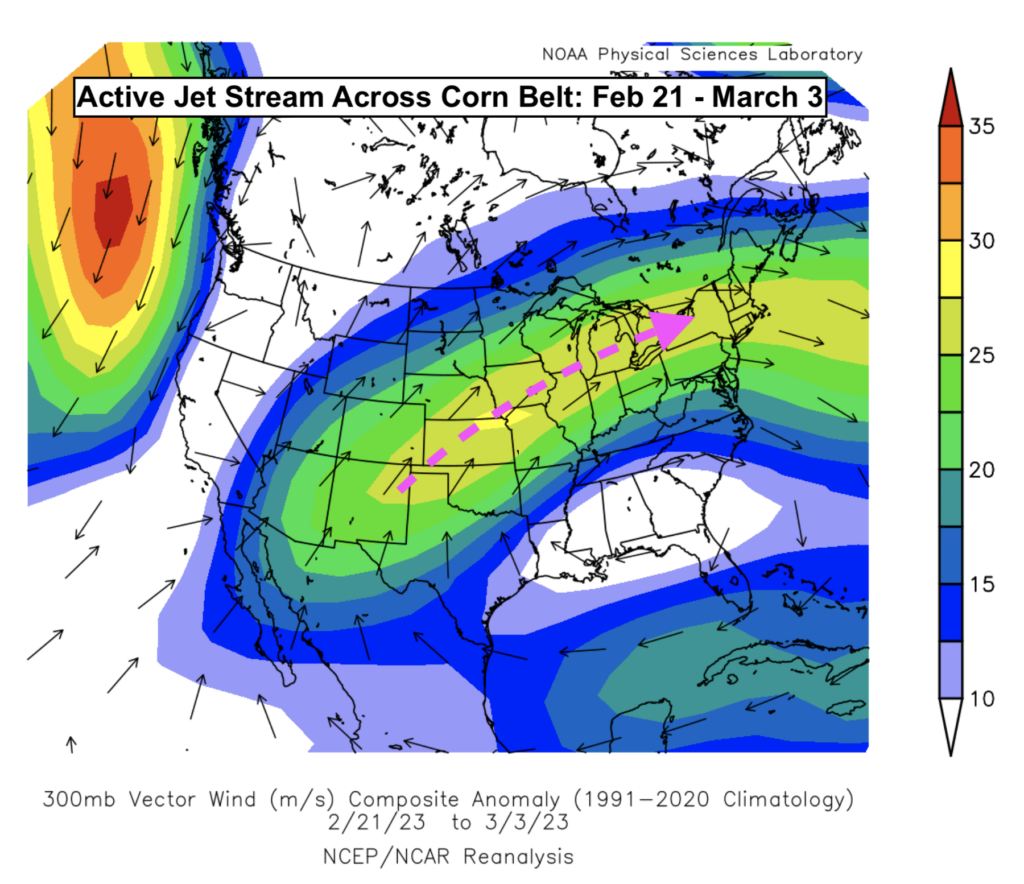

Figure 1: Jet stream anomalies averaged across 2/21/23 through 3/3/23. Note the strong flow over Illinois.

That strong jet stream, characterized by very fast winds miles aloft in the atmosphere, influenced several inclement weather events across Illinois to end February. Pictured above is the anomalously strong jet stream which focused across the Midwest in late February. This helped steer repeated storm tracks through Illinois. An ice-storm impacted portions of northern Illinois on February 22nd leaving thousands of Illinoisans without power. On February 27th, a potent low-pressure fueled the development of severe storms across central and northern Illinois, some of which produced brief tornadoes. One of those tornadoes was observed and photographed by this meteorologist at 8:30am with coffee still in hand – the first AM tornado of my career. That tornado is pictured below – coffee excluded.

Figure 2: 2/27/23 Tornado touches down in corn fields near Champaign, IL. -Matt Reardon

As the calendar flipped to March, the active pattern continued. Yet another potent storm system swept across Illinois on Friday, March 3rd, bringing high wind, heavy snow, and rainfall across the eastern Corn Belt. If there’s one benefit to this active stretch of weather across the Corn Belt, it’s that we’ve significantly improved soil moisture profiles across the area. See the image below for root-zone soil moisture estimates from February 5th versus March 5th just a month later.

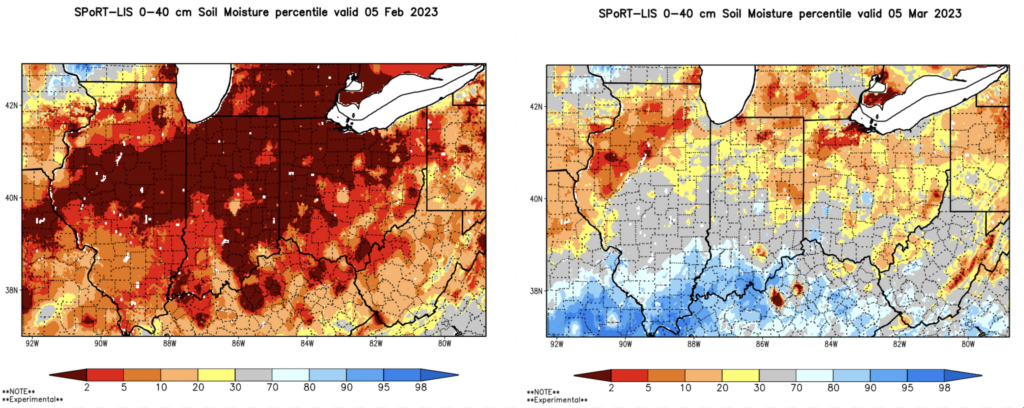

Figure 3: Comparing NASA Estimated Rootzone Soil Moisture; Left (Feb 5th); Right (March 5th)

Gone are the widespread deficits across the eastern Corn Belt, with only lingering dry patches across northwest Illinois. Removing this dryness was a priority for us here in the Midwest as it reduces drought risk just as we enter a new growing season.

Forecast

Temperatures have been warmer throughout Illinois over the last two months. That trend will change in March. Models have consistently forecast a colder pattern across the eastern US through mid-March – this includes Illinois. Another system will pass through the state late Thursday (3/9) into Friday (3/10) bringing more rainfall to the state – with snow expected in far northern counties. The cooler pattern will settle in next week which could bring associated winter precipitation chances through the middle of the month.

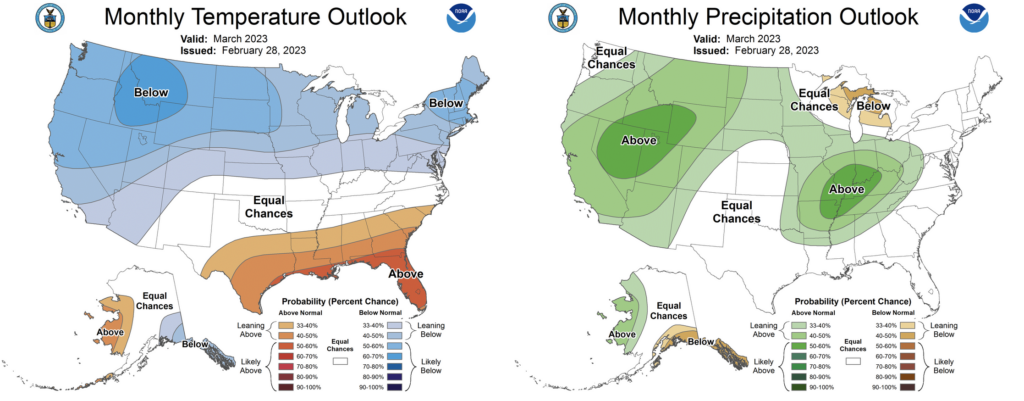

In the longer-term, long-range forecast models have been consistent in their signal for a wetter spring across the Corn Belt. This has many expecting tighter planting windows this year. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) released their latest March outlook (pictured below).

Figure 4: Climate Prediction Center (CPC) March Outlook

Complicating this forecast is the ongoing transition out of La Niña in the Pacific Ocean. La Niña typically promotes wetter conditions across the Ohio River Valley in spring and we saw similar effects last year in 2022 with delayed planting across major growing regions in the central US. It’s possible some of these long-range forecast models are bias toward a similar pattern given the current, yet fading, La Niña state in the Pacific. That La Niña is expected to officially fade to neutral by April. I have lower confidence in those wet forecasts through April and May as a result. The ECMWF (European weather model) seasonal forecast has even shifted toward a more average precipitation pattern for the month of April across Illinois. This would increase chances for sufficient windows in April after what looks to be wet and cooler March.

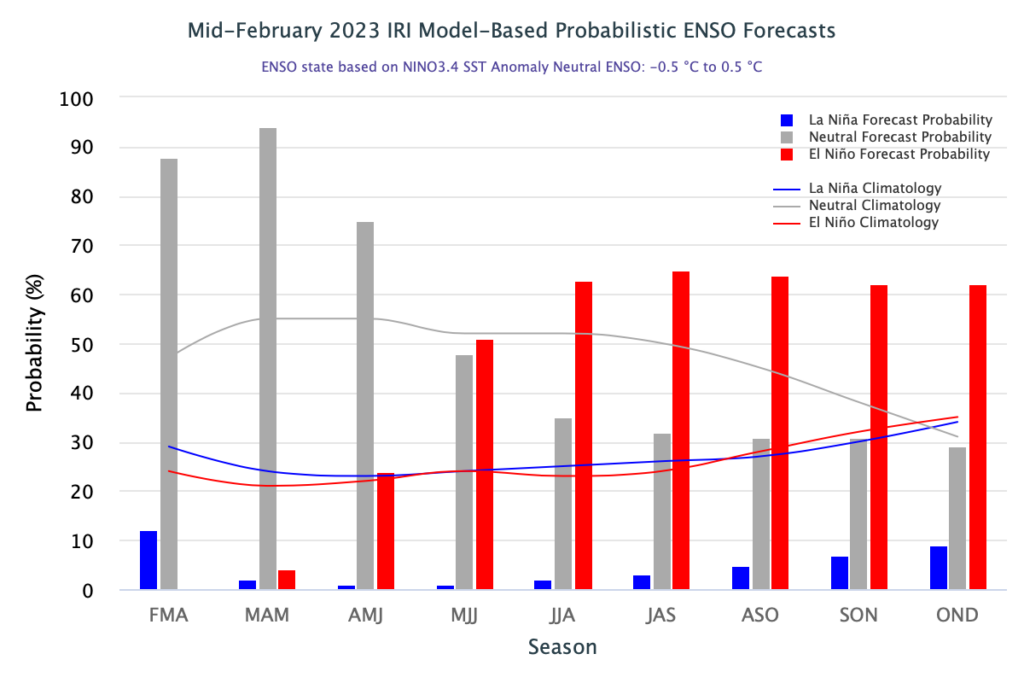

With a fading La Niña signal, I am expecting shorter term influences on the atmosphere to play a larger role this spring. See image below for the IRI ENSO Forecast depicting rapidly fading La Niña probabilities (blue) as we move into the spring months.

Figure 5: IRI ENSO Forecast 2023

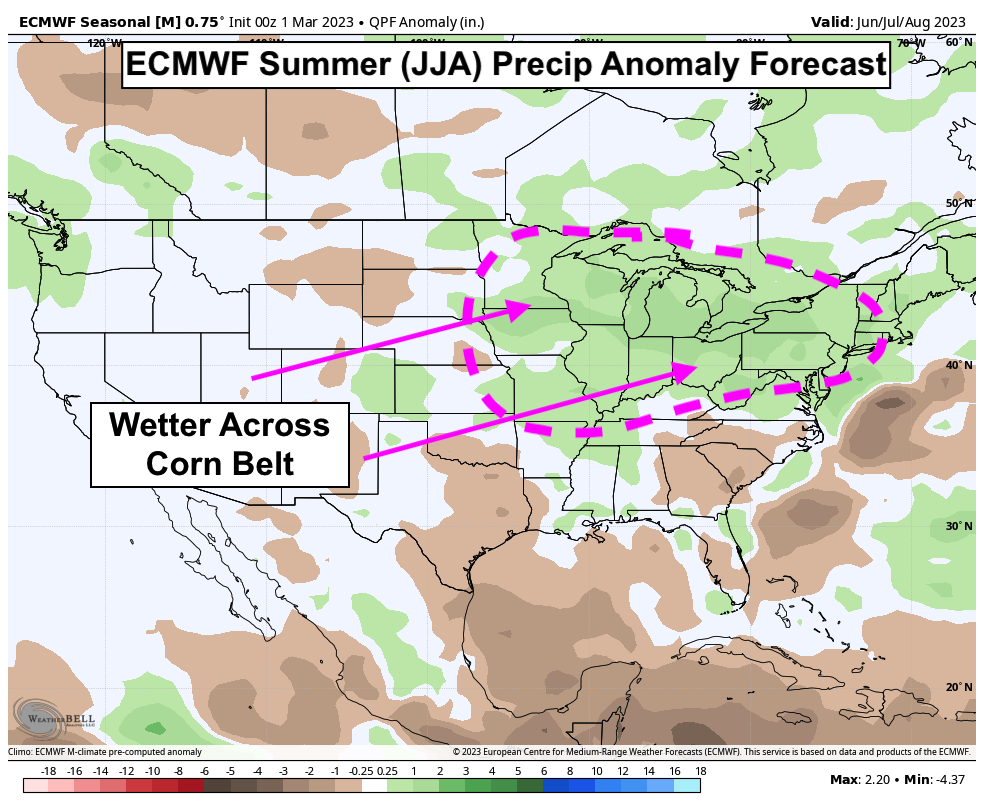

You’ll notice that throughout the forecast above, El Niño probabilities (red) steadily increase through the year. Forecast probabilities peak around 65% through late summer of 2023. Should we enter an El Niño in summer 2023 that would improve rainfall chances across the central US and could yield a more productive growing season – with less risk of drought. Regardless, the impending exit of La Niña will help to reduce chronic drought risk across the US this summer. Long-range seasonal forecasting remains an inexact science, but I can say that I’m less worried about Central US drought this year than I was going into the 2022 growing season. See the image below for the ECMWF Seasonal Forecast for June, July, and August.

Figure 6: ECMWF Seasonal Forecast (Summer)

Have a great March!

and then

and then