August and September are the peak months for hurricane activity, both in the Eastern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Last month saw two significant storms impact the United States. First, Tropical Storm Hilary, having weakened from a major hurricane just days earlier, made landfall south of San Diego, CA, on August 20th. Strong winds and torrential rain downed trees, flooded towns, and caused numerous mudslides in Southern California. Some desert locations received nearly a year’s worth of rainfall in one weekend. Just a week later, the Atlantic roared to life as a powerful hurricane developed in the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Idalia would peak at Category 4 strength before weakening slightly as it made landfall in the Big Bend area of Florida on August 30th. Damaging winds, storm-surge, flooding rains, and even a few tornadoes caused serious damage to coastal areas in Northern Florida in addition to heavy rains in Georgia and the Carolinas.

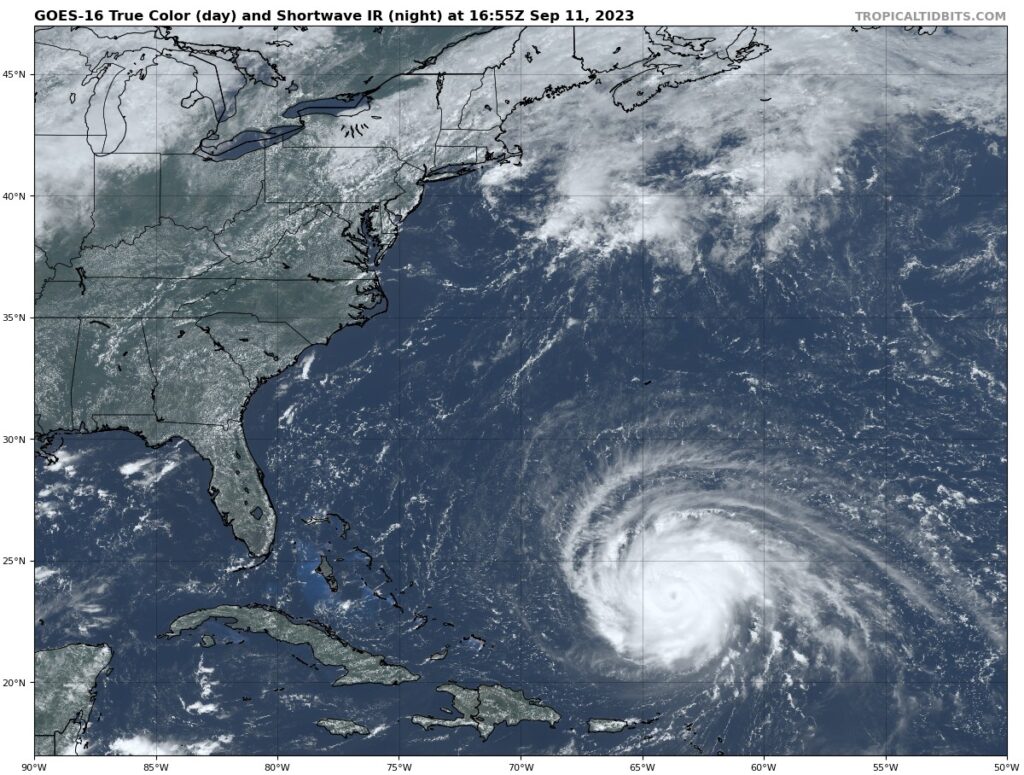

The tropics remain active here in September. Hurricane Lee, a major hurricane as of this writing, is spinning vigorously in the Atlantic. Current forecast tracks take Lee very near to the New England coast this weekend (9/16 – 9/17) which could bring at least adjacent impacts to those states – strong winds, rain, and storm-surge. Still, forecasting the track of these storms many days out is difficult and communities in the Northeast US and Nova Scotia and will need to be prepared for track updates.

Meanwhile, closer to home, August began wet across the Mississippi River Valley. As our attention shifted to tropical activity along both coasts, conditions trended hotter and drier across the Midwest in the latter half of the month. This growing season feels increasingly like an experiment to determine what sort of crop can be grown when the only significant rainfall received is during those crucial late July and early August windows – I guess we’ll find out soon enough. USDA’s Crop Progress conditions seem to suggest the recent hot spell didn’t significantly impact crops. That said there are localized areas (KS, MN, etc.) that missed out on early August rains which are likely struggling at this time – especially soybeans.

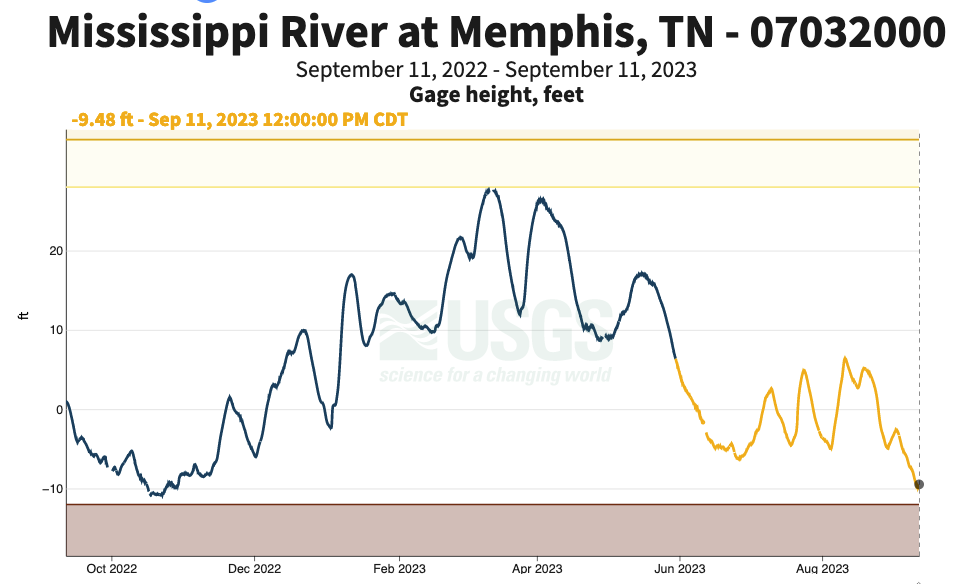

With recent dryness across the Mississippi River Valley, river levels have dropped to concerning lows. Last October, near-record low river levels along the Mississippi River reduced barge traffic, even stalling it outright at times, which disrupted vital agricultural supply chains. That risk has unfortunately returned this fall with levels nearing the lows we saw last year. Now that crops are nearing full maturity, this is quickly becoming my chief weather concern for production agriculture in the Central US. Unfortunately for the river, the near-term forecast for the rest of the month doesn’t showcase much rain for the Midwest. While this past Monday (9/11) saw widespread shower activity across the state, forecast models depict a return to drier conditions through the week – and possibly into next. The Climate Prediction Center’s forecast for the third week of the month (Sep 18th – Sep 24nd) includes the possibility of that rainfall dearth persisting until the last week of September.

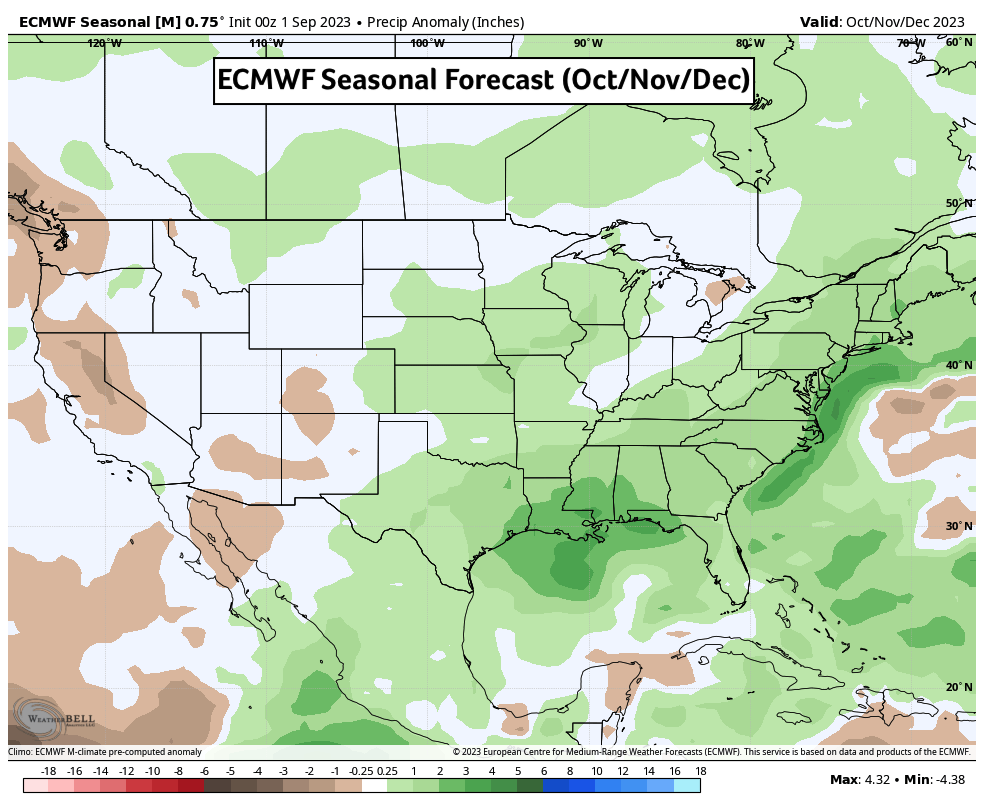

El Niño raises the chance for above average precipitation along the Mississippi Valley in fall. Coincidentally, our ongoing El Niño continues to strengthen in the Pacific Ocean with forecasts suggesting further development toward a strong or very-strong peak sometime this winter. Meteorological fall (Sep/Oct/Nov) has just begun, and while it’s been dry to date, seasonal forecasts for October and November suggest a materialization of those increased precipitation chances. That could be good news for Mississippi River levels but could pose soil workability issues and tighter harvest windows. If the tropics remain active into October, that could increase the possibility of a Gulf of Mexico storm making its way into the Midwest as a remnant low. Those can deliver inclement rain and even gusty winds which can disrupt harvest plans.

Looking beyond harvest toward winter months, El Niño winters in Illinois and the Upper-Midwest tend to run on the warmer and drier side. Those correlations aren’t particularly strong, however, and some seasonal model guidance suggests even chances for both temperature and precipitation anomalies. Each El Niño is different and that won’t change with this episode. We typically expect reduced Atlantic hurricane activity with a background El Niño state but that hasn’t held true this season due to anomalous warmth in the tropical Atlantic Ocean waters. It’s possible that competing influences are winning the day while El Niño continues to strengthen. With the growing season winding down, we begin those familiar autumn discussions of hurricanes and harvest. Soon enough, we’ll be tracking snowstorms and Santa Claus.

Matt Reardon

matt.reardon@nutrien.com

and then

and then