In the past 5 years, Illinois soybean yields have risen exponentially compared to the previous 10 – 15 years. A lot of this increase can be attributed to modern breeding programs; however, modern management has also improved. High-yield producers view a crop as a series of decisions, throughout different growth stages, that add up to improved yields. These growth stages usually include “early,” “middle,” “late” and now – R4.5.

Early Season: Anything associated with improving emergence and early vigor.

- Seed treatments allow for early planting dates, while ensuring adequate stands.

- Tillage improves seed-to-soil contact and reduces early season root restriction.

- Starter fertilizers provide plant available nutrients close to the root zone.

- Residual herbicides reduce early season pressures.

Middle Season: Anything associated with reducing developmental stresses.

- Proper variety placement/selection (genetic by environment).

- Weed suppression allows more nutrients, water and sunlight to be available to soybean plants.

- Fertility is crucial. Feed the crop; don’t just expect it to live and thrive off the leftover nutrients from the previous corn crop.

Late Season: Late season management has been limited to a fungicide and insecticide application at R3-R4 growth stages. These practices can reduce stress during bloom and pod development. Soybean producers understand the importance of keeping the vegetation growth strong and plentiful during mid to late grain fill. In more recent years, seed treatments such as ILeVO® are an early season management decision, however, they provide value against SDS which impacts late season development.

Applying a fungicide at R3-R4 protects the leaves. The typical follow-up question is, “How long will the protection last?” If typical products, at best, can provide protection for two stages, how much impact will disease have on the crop after that protection wanes and is another application justified?

Applying an insecticide at R3-R4 protects foliage from leaf and pod feeding insects. The typical follow-up question is “How long will it last?” There is a wide range of types and quality of products, and at best protection can be a few weeks.

R4.5 and Beyond: Stress can still impact yield at growth stage 4.5 and beyond.

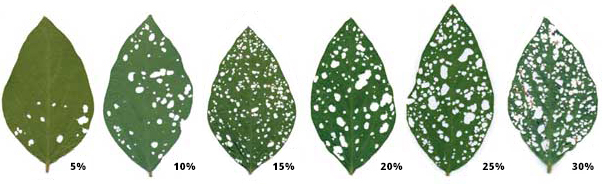

Figure 1 represents the different levels of soybean leaf defoliation Note: For economic impact these levels must be observed across all leaves. The insects typically causing this issue can also impact pod quality, seed quality and ultimate pod retention. These entry wounds can also provide entry points for disease and viruses. The takeaway from this chart is how important the plant’s “solar panels” are to building yield. The answer is very important.

Figure 1: Examples of soybean leaf defoliation.

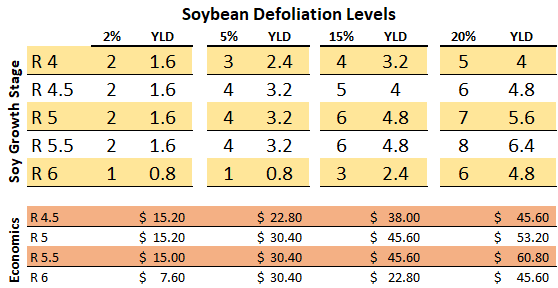

Figure 2 is a chart from Purdue University Extension soybean defoliation studies based on 80 bu/A beans and $9.50/bu. This information reflects the value or the importance of protecting the vegetative engine that supports high yield. The chart supports that minor vegetative impact from R 4.5-R5.5 has some impact on final yield or profitability. However, if vegetation is significantly impacted 15 – 20 percent yield and profitability are strongly impacted.

Figure 2: Purdue University Extension soybean defoliation studies.

Moving forward, there’s going to be more talk and evaluation about managing a soybean crop during 4.5 and beyond. It’s important to remember that like corn yields, soybean yields are greatly impacted by late-season stress. These stresses can impact pod retention and pod fill.

and then

and then